One of the most frustrating things about the recent massive O2 blackout (apart from their refusal to give an ETA) was the fact they wouldn’t even admit what was wrong and why people couldn’t get any signal. The internet was awash with unfounded supposition (a pre-Olympics volume update was a favourite theory) and the lack of any firm statement from the networks only served to encourage things.

Although O2 are refusing to answer press questions about what exactly went wrong, we know that you are a curious bunch so we looked into it a bit more to try and work out all we can about the background to the outage. As promised previously, here’s all we know about the cause of the problem informed by our sources, statements from industry insiders and some educated guesses.

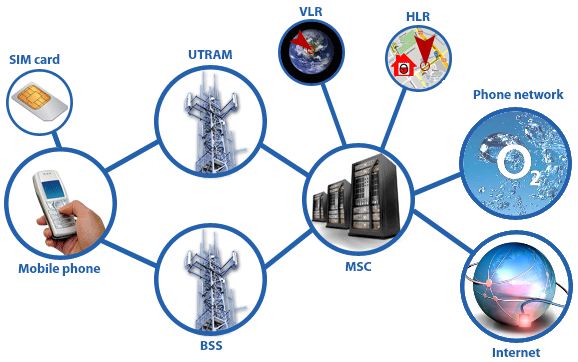

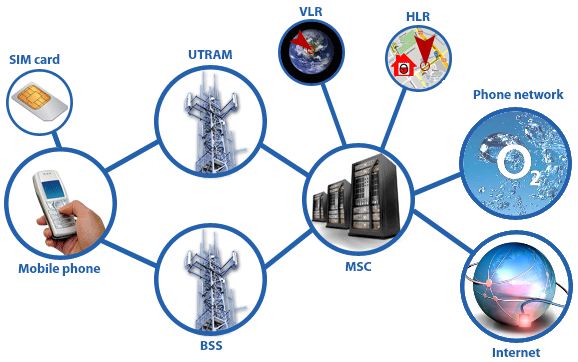

Too start with, we have to explain a little about the workings and structure of modern GSM mobile networks. The core of all mobile networks is the Network Switching Subsystem (NSS) which handles all aspects of call switching (think of it like a modern day operator, connecting users to each other). Central to this is the Mobile Switching Centre (MSC) which effectively sets and and releases all connections – it routes all services across the network. Think of it a bit like your router at home which lets you connect your PCs, laptops, games consoles and smartphones to the internet through one broadband connection. Just as it lets all your devices find this website when you type in mobilenetworkcomparison.co.uk, the MSC routes calls and texts to the right place on the network.

Connected to the MSC are complicated pieces of hardware like the base station subsystem (BSS) which allows 2G mobile phones to communicate with the NSS. It consists of antennae, transceivers, encryption software and transcoders. It send/receives all the communications between mobile handsets and the main networks (the phone network and the internet). Mainly, it has to handle the conversion of the wireless radiowaves sent to and from phones into a form that can be understood by the computerised digital systems at the core of the network. There is also a 3G equivalent of the BSS called the UMTS Terrestrial Radio Access Network (UTRAN). Another important piece of equipment is the Visitor Location Register (VLR) which stores information about the physical location of each subscriber so the network knows where to find each phone.

The most relevant part to us is the Home Location Register (HLR) which holds information about each subscriber of the network. It has the details of all the registered SIM cards and mobile numbers as well as other information used to identify users. Some of its functions are updating the VLRs with mobile phones’ locations (each phone can only be on one VLR at a time), and communicating with the MSC.

It also authenticates users onto the network. the HLR includes information on supplementary services, authentication credentials and subscriber profile information such as details about APN (Access Point Names) which provide data access. For example, when you try to use the internet on your phone, O2 checks with the HLR to see whether you have permission to use the APN which provides web access. If the HLR is not working properly you won’t be able to get online.

It seems the problem was that the O2 HLR was not working properly or completely unreachable and hence people couldn’t get a connection to a cell tower as they could not be authenticated. Big networks have HLRs that are made up of several components including a gateway/frontend, backend servers as well as the database they get their information from.

We don’t know all the details about how O2 sets up its HLR but internal documents confirm that the HLR includes information on supplementary services, authentication credentials and subscriber profile information such as details about APN (Access Point Names) which provide data access. For example, when you try to use the internet on your phone, O2 checks with the HLR to see whether you have permission to use the APN which provides web access. If the HLR is not working properly you won’t be able to get online.

We now have enough information to be reasonably confident that the HLR was at fault. More specifically, we are pretty sure that the problem was with the database part of the HLR. The database for O2‘s HLR is run by the huge Swedish company Ericsson. Core provisioning systems were first outsourced to them by O2 in 2009 and they run large portions of the network’s backend.

What seems to have happened with the O2 outage is that the database was being transitioned and consolidated into a new Centralized User Database (CUDB). According to Ericsson, this CDDB,

provides a single point of access and administration to the subscriber data. CUDB node is based on a Distributed Cluster Architecture which guarantees high capacity with an optimal footprint and real time availability. CUDB ensures data consistency and integrity and redundancy mechanisms. The physical and logical distribution of the data is transparent to any data user (HLR/AUC, application servers, BSS). Communication with data users is through standard LDAP protocol.

In this instance though, the CDDB became inaccessible and instead of being a “single point of access and administration”, it turned out to be the sole point of failure. Without access to the HLR’s database, mobile phones weren’t able to connect to the central network via the MSC and they lost all service. The fact that the problem wasn’t with the actual network infrastructure in any particular place explains perfectly why the outage wasn’t restricted to any particular region. And knowing that it was due to an error with the authentication database also should make it clearer why people were affected randomly – it all depended on whether you were already connected to the HLR or whether you could get through rather than how close you were to a cell tower or what type of phone you had.

This isn’t the first time problems with a network’s HLR have cause downtime. Ericsson’s big rival Alcatel Lucent supplied Orange France with HLR systems that broke down and caused a 12 hour outage for 26 million users earlier in July. Also, Vodafone suffered a mass outage back in 2006 when its HLR went down. But anyway, there you have it – a bit more of an insight into how mobile networks actually operate and a straightforward answer to what went wrong in the huge O2 outage.

Did that explanation make sense or do you have another theory? Do you think you’ve learned something about the operation of mobile phone networks? Are you worried about similar errors occurring again on O2 or another network? Let us know below.

If there were any doubts remaining about the mobile market in China, the latest figures will surely put them to rest. Needham & Company analyst Charlie Wolf’s quarterly report came out last month as confirmed that China’s stratospheric boom in smartphone sales shows no sign of letting up any time soon. With an ever growing middle class and their new-found disposable income as well as technological advances and falling hardware prices, the latest figures are all but inevitable. The report claims that there are now over 33 million smartphones shipped in China every quarter. That’s a gargantuan year-on-year increase of 164% and a yearly equivalent of over 130 million. The same time last year, just over 10 million smartphones were sold and even in the previous quarter the figures were only just over 25 million. At this rate, we could easily see 40 million smartphones shipped in China in the next quarterly report.

If there were any doubts remaining about the mobile market in China, the latest figures will surely put them to rest. Needham & Company analyst Charlie Wolf’s quarterly report came out last month as confirmed that China’s stratospheric boom in smartphone sales shows no sign of letting up any time soon. With an ever growing middle class and their new-found disposable income as well as technological advances and falling hardware prices, the latest figures are all but inevitable. The report claims that there are now over 33 million smartphones shipped in China every quarter. That’s a gargantuan year-on-year increase of 164% and a yearly equivalent of over 130 million. The same time last year, just over 10 million smartphones were sold and even in the previous quarter the figures were only just over 25 million. At this rate, we could easily see 40 million smartphones shipped in China in the next quarterly report.

Recent Comments